In this new blog series, we give the floor to researchers engaged in valorization activities within the sports technology and innovation field at Ghent University. In this way we want to provide insight into what is brewing behind the scenes. For once, we put the researcher under the microscope.

For this first blog we have a chat with dr. Simon Helleputte.

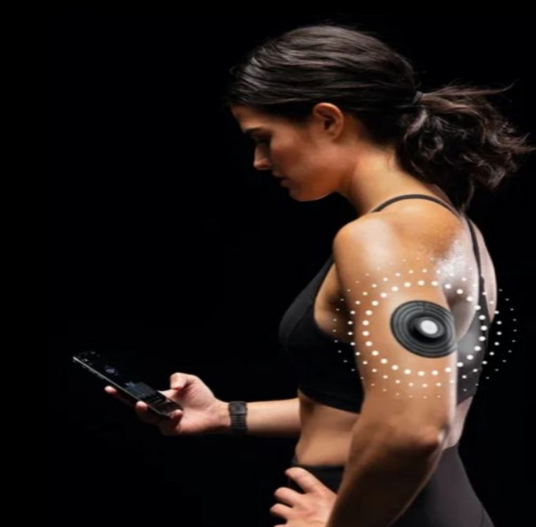

Simon Helleputte is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences and the Department of Movement and Sports Sciences. He is currently working with Sport Vlaanderen on a project on continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Several Belgian elite Olympic athletes are wearing non-invasive glucose sensors that continuously measure interstitial glucose levels for a two-week period.

Continuous glucose monitoring in elite athletes: yes or no?

Little is currently known about how and whether continuous glucose measurements can add value to the training and/or sports nutrition plan of non-diabetic (elite) athletes. The technology, however, has been around for some time and is already widely marketed, but research on the use and impact of these measurements in a sports context is scarce. Simon’s project aims to change this. In order to do so, several research questions are key and need to be explored:

- Can we optimize the timing of carbohydrate intake and supplementation before exercise with regards to subjective experience (the athlete’s sensations) and objective measures (performance) of the athlete during exercise?

- Can we improve the timing, quality and quantity of sports nutrition during exercise in relation to glucose levels as obtained with CGM?

- Can we use CGM to detect – and potentially avoid – (too) low glucose levels before, during or after exercise, potentially improving the performance and recovery of the athlete?

“The study will definitely have an impact. Any findings, positive or negative, will be valuable. It will show us what we can and should really expect from those sensors; what information they provide us with is useful? But equally important: What information they provide us with is not useful?”

The project will give us fundamental scientific insights into how capable the body is in maintaining blood sugar levels during all forms of exercise. At the same time, the results will show which dietary recommendations are overrated during exercise and which are absolutely not. Therefore, this project goes hand in hand with nutritional advice.

Little is currently known about how and whether continuous glucose measurements can add value to the training of (elite) athletes.

Not an easy schedule to make

The athletes involved in the study are primarily “endurance athletes with high metabolic demands”. Marathon runners, rowers, (track) cyclists, sailors… The project takes into account the athletes’ individual timeline to Paris i.e., training camps, specific focus periods, and competition.

“The biggest challenge for me is the day-to-day management of the project. I work with many different athletes simultaneously, and I often communicate with their entourage. Coaches and dieticians need to be involved because they communicate with the athlete. In terms of scheduling, it can sometimes be difficult to manage. Last-minute changes are very common, so it’s nearly impossible to schedule a meeting in advance. I come from a rather tightly scheduled research background during my past PhD, so that’s definitely a challenge.”

What exactly to communicate to athletes and their team, is not so simple either. Findings must be distilled into comprehensible advice that is sufficiently supported by evidence. Overinterpretations or conclusions drawn too quickly can cause the athlete to worry unnecessarily!

“A psychological aspect as well is that the athlete “should not get lost in the data”. Because that sensor is like Big Brother. For two weeks it continuously measures your blood sugar levels. Everything you eat and drink can be seen. And if, as an athlete, you tend to worry or get anxious easily, that does pose a risk. After all, they do not posses the necessary knowledge about metabolism and physiology to make the right interpretations – and that’s why I am here.”

The athletes participating in the study will directly benefit from the collected data and the results, as do their coaches.

Post-monitoring plans

“This project is now primarily focused on the run-up to Paris ‘24. Then we will look further into which research questions and application areas there are left. For the moment, it is glucose, but there are also other metabolites such as lactate and ketones. Those sensors are already on their way, so to speak, but not yet ready for the market.”

After the Olympics, a scientific report will be formulated from the BOIC to the broader Belgian sport entourage.

The athletes participating in the study will directly benefit from the collected data and the results, as do their coaches. Athlete coaches sometimes have as many as 10 athletes under their supervision, hence they will be able to further apply the acquired knowledge.

Any findings, positive or negative, will be valuable. It will show us what we can and should really expect from those sensors; what information they provide us with, is useful? But equally important: What information they provide us with, is not useful?

Valorizations to keep an eye on

“I don’t want to brag about our own institution, but I think ‘OnTracx’ is a great example of a possible successful valorization. The problem of injuries in runners is a never-ending concern, so imagine that we can visibly quantify a runner’s load and its relationship to injuries. Can we intervene? Could we prevent injuries? I think that’s super interesting.”

“And so is the PACE project! It’s a nice example as well. Because it enables you to use science to compile data that would otherwise be almost impossible to oversee, and allows you to find out whether strategies within a particular sport can be optimized – in this case, a pacing strategy in track cycling. The results are quite promising.”